Rape and sexual assault – Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009

Under Scots Law, rape is a crime considered so serious that it could, possibly, result in a life sentence for the perpetrator. It’s defined in the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 as penetration by the penis of the vagina, mouth or anus without consent, or the reasonable belief of consent. It also clearly states that this consent must be by ‘free agreement’, which means that a woman should not be forced, coerced in any way, misled, or duped. It also means that if someone is too drunk or under the influence of drugs to consent, then that consent does not exist.

If the woman is sleeping or is unconscious (perhaps because of alcohol or drugs) then there is no consent. The legislation also states that consent can be withdrawn at any time, even if there was consent at the beginning of the act.

There are other offences where the focus is on consent by free agreement. These include:

- Sexual assault by penetration – where there is penetration by other parts of the body (not the penis), or with objects.

- Sexual assault

- Sexual coercion

- Sexual exposure

- Voyeurism

The Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 can be accessed at Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 (legislation.gov.uk)

The impact of rape on the life of the survivor

Rape happens when a man forces, coerces, or manipulates a woman into a sexual act (as described above) without her consent. Although this is a sexual act, rape is not a result of lust, or desire but happens because of a desire to control or have power over the woman. There are many myths which tell us that men cannot control themselves, cannot stop a sexual act once it has begun, or ‘need’ to have sexual satisfaction. None of this is true.

Because of the nature of the crime of rape, the feelings of violation experienced by the woman, and her reactions in the immediate aftermath and in the longer term, may be unexpected. This can be because there is a societal belief that there is a ‘right way’ and a ‘wrong way’ to react after a rape.

Rape is a traumatic event and people experience trauma differently. Similarly, everyone has different ways of coping in the aftermath of rape or sexual assault, as well as in the longer term. In the immediate aftermath of a rape, the survivor may feel:

- Shock, numbness, blank, inability to focus, exhausted, falling asleep

- Calmness, able to answer questions, able to communicate clearly

- Distress, weeping, anger, confusion, inability to understand what is being asked/said to her

- Denial, minimising the event, avoidance, needing to escape

- Inability to recall anything that has happened, shaking, hypervigilant, easily startled

All of these are normal reactions to the abnormal and traumatic event that has taken place. Survivors may experience some or all of these feelings.

It’s common for survivors to question how they responded in the moment they were attacked. We may have heard about the ‘fight or flight’ response that people have at times like this, but in fact the most common reaction that women have is that they freeze. Research has shown that 70% of survivors of rape froze in the moment of the trauma (Moller et al, 2017; Eaton, 2019). In fact, there are several ways in which trauma survivors react in the moment that are often unknown:

Fight: This is what society expects; women are expected to stand up and fight the attacker off, to scream and shout. Women take self defence classes for this reason and have all manner of ‘defence’ items that they use like walking home with their keys clasped in their hands, carrying tins of soup or beans in a carrier bag that they can swing at the attacker, or rape alarms that can be carried in the pocket. The ‘fight’ response is not common.

Flight: If fighting is not possible, flight is the next expected response. Women are expected to run away, or indeed avoid any areas that may be dark, lonely, or ‘dangerous’. Women’s inability to flee can sometimes be questioned, especially when the woman is young, or is a regular jogger. But the ‘flight’ response is also not common and the woman’s level of fitness or age does not matter at the point of trauma.

Freeze: In reality, this is the most common reaction (see reference above). Survivors often describe freezing as feeling ‘paralysed’ by fear. They describe being unable to speak or shout, feeling numb and sometimes feeling disembodied or dissociated from what is happening. This reaction in the moment of trauma is because the brain has changed the way it functions so that it can focus solely on survival.

Friend: This is not a common response but happens more often in situations where the perpetrator is known to the woman. She tries to calm or placate him, to reason with him, sometimes in a way that focuses on his own safety. For example, a woman may reason that he will get into trouble, or that it’s not worth it to put himself in danger. In cases of intimate partner sexual violence, the woman may use this to calm the perpetrator down before the sex act takes place to avoid physical injury.

Flop: This is sometimes called ‘tonic immobility’ where the survivor may faint, pass out or become limp and unresponsive. Tonic immobility tends to happen where the fear or terror of the situation is so great that the woman’s body shuts down in order to protect her.

What’s happening in the brain in the moment of trauma?

The human brain is amazing. It keeps us alive, tells us when we are hungry, thirsty, tired, lets us enjoy certain things, and let us laugh, and cry. But the sole purpose of the brain is to keep us alive. When a threat is perceived, the frontal lobe of the brain – where the brain processes learning, decision making, and problem solving – is too slow to make decisions about safety. The limbic system takes over. It’s a more primitive part of the brain and contains the amygdala, the brain’s ‘fire alarm’. When fear or threat is sensed, that alarm sounds. Other parts of the limbic system respond: the hypothalamus and the brain stem inform the autonomic nervous system to get the body ready to respond. Adrenaline and cortisol are released which increase the heart rate, blood pressure and breathing. The body is ready to respond to the threat. If the body is unable to respond because the senses feel that it cannot fight or flee, another reaction is to freeze.

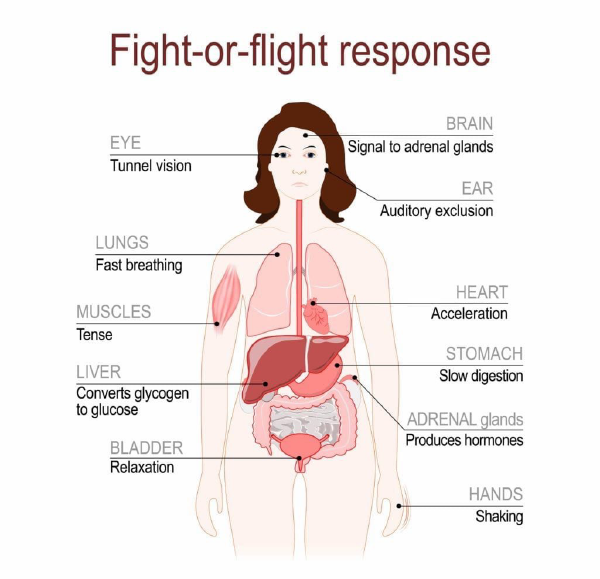

This diagram shows how the body responds to fear. Most people will recognise some of these responses when experiencing high levels of stress. When threats are perceived, the body and brain work together to respond in a way that will best ensure survival.

Diagram ‘Fight or Flight Response’[2]

When women experience the trauma of sexual violence, freezing is the most common response. The ‘freeze’ reaction has the opposite effect to the autonomic nervous system’s response in that it slows down breathing so that the survivor may feel she cannot breathe, heart rate drops, digestion closes down, and the survivor may feel that her bowel or bladder wants to empty.

The survivor may have no idea that any of this is happening because it takes place so quickly and with little or no input from the frontal lobe of the brain. The body is in survival mode.

Another aspect of this process is that the hippocampus, which under normal circumstances processes short term memory, can be interrupted in its normal job by stress and the release of cortisol. This means that processing of memory is interrupted, and survivors are often left with only sensory memories, remembering a sound, smell, a feeling on the skin or a colour or texture. Because of the nature of these sensory memories, they can become intrusive and can contribute to anxiety, flashbacks, and panic attacks.

Acknowledging the trauma that has been experienced and understanding what happens in the brain and body in the moment of the attack, can help a survivor begin that process of recovery and healing. It can help make sense of the feelings experienced during and after the attack. The experience of sexual violence is often described by survivors to be a violation of the most intimate and private parts of the body. There are many myths surrounding sexual violence, usually related to unrealistic expectations of women’s behaviour and this so often results in victim blaming attitudes from others.

There is no ‘right’ response, no predictable way to react to a rape or sexual assault. There are common physical and psychological reactions (see above) that are responses to what is happening within the brain’s limbic system. For example, because of the way the brain responds to trauma, common reactions include:

- Freezing

- Not reporting the rape, or delaying the report

- Having gaps in memory

- Being unable to recall what happened during or after the attack

- Showing no physical injuries after the attack – often because of freezing

- Giving inconsistent statements to police, remembering the attack differently as time passes

- Continuing in a relationship with the perpetrator

- Denying or minimising the trauma

Women can appear calm and in control, they can be weeping uncontrollably, silent and in shock, angry and aggressive, afraid, and shaking. These are normal responses to a very abnormal experience that the woman has undergone.

“Women report greater degrees of emotional numbing, lower range of feelings, avoidance responses, and experience higher levels of psychological reactivity to traumatic stimuli.” [3]

The impact of rape and sexual assault may depend on a number of factors. These include (but are not limited to):

- The previous relationship with the perpetrator (if there was any previous relationship)

- Whether the survivor had experienced trauma previously

- The nature of the attack

- How long it lasted, was it a ‘one off’ experience or ongoing abuse over an extended period, such as intimate partner sexual violence or childhood sexual abuse

- How people around the survivor, family, friends, partner, and others responded when the rape was disclosed

The effects of the trauma can be felt in the immediate aftermath of the rape and carry on into the longer term. These can be both physical and psychological and may include:

- Shock, anger, and irritability

- Fear and anxiety sometimes leading to panic attacks

- Sleep disruption including nightmares

- Intrusive memories or reliving the incident

- Hyperalertness and hypervigilance

- Isolation, numbness, detachment

- Fear of being out of control of every part of your life

- Minimising the event, or denial that it happened, or that it was serious – for example, “it was just something that got out of hand.”

- Feeling betrayed

- A sense of shame

The majority of women are raped or sexually assaulted by someone they know. This can add to the trauma experienced by the survivor by creating a world where everything has to be questioned: trust, safety, betrayal. It can also compound the sense of shame, self-blame and guilt felt by the woman. This is often why women are reluctant to disclose the rape to police, but also to those close to her.

In her 1992 book ‘Trauma and Recovery’, Dr Judith Herman writes that trauma enhances the need for protective relationships, but that one of the harms of trauma is that it also violates human connection. This can make such relationships difficult to establish or maintain.

At Beira’s Place, we work with the Herman Model, building safety, trust and connections in a space where women can connect with their support workers, and with other women through our group work programme. Safe connections are crucial to recovery and healing, and we aim to build them within a safe, women only environment.

[1] Public Speaking and the Fight or Flight Response – Stephenson Coaching

[2] Fight or Flight | HowStuffWorks

[3] Emotional Processing in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Litz, BT, Orsillo, SM, Kaloupet D, and Weathers, F (2000)